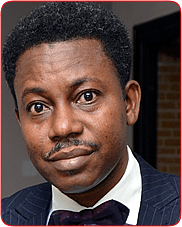

ABOUT

I am a strategic communications consultant, media expert, and storyteller dedicated to helping organizations and brands connect with audiences through compelling narratives and insightful media strategies.

Scroll right

I was born in Ayeye, Ibadan, the capital of the old Oyo State in the evening of Thursday, October 14, 1965. My mother, Elizabeth Onayoade (nee Aderemi) was preparing to go to vigil at the C&S Church, Inalende when her pregnancy water broke. My birth was a sweet relief to her, having endured six agonising years of cessation after the birth of her first child before I came forth. It was her long-suffering and forbearance; the jeering and taunting towards her long delay, that prompted my name: Adesanya, which literally translated as God assuages my suffering.

My early years were spent in Inalende, a few years after my birth. The rented house, a face-me-face you story-building in a run-down neighbourhood, was inhabited by people of all shades who took out either one room or room and palour, and shared facilities like clothing lines (for spreading washed cloths), toilets and bathrooms which sometimes witnessed queues with buckets, especially in the morning and the kitchen which was another arena for women gossips and small talks and balconies where children had their rough plays or games. The tenants were mainly traders, artisans and school teachers who lived in harmony with occasional outsbursts from warring wives who uttered inanities or quarreled about the space or missing items in the common kitchen or a neighbour’s misdmeanour that went unchecked. My father, who rented the head room and the next (room and palour) on the upper floor was the caretaker of the 20-room house, and had the privilege of issuing out instructions about cleanliness and utility bill sharing among others. He had his own respect, and you could see troublesome children on the corridor scurrying into their rooms with shouts of caretaker nbo (caretaker is coming).

The house, numbered N3/696B after the colonial government British house numbering system, nestled on a hilly flatland that was inaccesible to vehicular movements. To get to your house in the neighbourhood required parking your vehicle, if you had one, on a motorable road some distance away, and trekked up convoluted steep.

Ibadan still evokes some nostalgia. Communal parenting was prevalent , highlighting the sentiment that it takes a village to raise a child. Bad behaviours could be punished by communal stakeholders, other than the parents such as uncles, aunts, neighbours, all taking responsibilities for the lives and welfare of the child. It was a life of school and football and sand dunes and okoto and agbalumo seeds.

Igbo Agala and Bower’s Tower are on one of the popular Ibadan hills. From the zenith of the tower which played host to tourists, you could see the whole Ibadan land spread out onto the outer reaches of the sky. You could navigate the tower from the road, but as we were wont to do as exuberant kids , if you navigated through the Igbo Agala, a long-held forestry reserve, you would romanticise with the steid ambience of the Forestry with its ecosystem of tall teak trees, and singing birds, the beetles roaming free on the ground; and of course meander through the numerous caked poohs littering the grounds of the reserve. “Ibadan l’omo o’mo layipo,” was a popular saying, so named because of the tower’s rotunda structure. Such remark was the accustomed jeers of the natives to visitors or new comers.

Inalende was communal in every sense of it. Apprenticeship freedom, naming and others socials didn’t require formal invite. Such event saw children huddled together around large bowls of rice as a couple of gazing sheep and goats waited in the wings to pounce on leftovers. Muslim and Christian festivals were celebrated by all irrespective of religious leaning. Ramadan festival was a period we looked forward to as children of christian faith because we would always participate in the eating of saari in the wee hours of the day when fasting muslims broke the day with meal and prayers. The evenings were filled with itinerant musicians playing weere, a Fuji genre laced with islamic lyrical underpinnings. Sikiru Ayinde, later called Barrister was a regular team lead of one of such musical groups.

During the Oke’Badan festival, children of the time developed the passion for trailing iconic masquerades such as Oloolu, Alapanshanpa and Atipako, all dreaded masquerades, from Inalende to Beere and Mapo, sucking in their acrobatic displays and guttural incantations. Women were forbidden from sighting them. Their rituals were cultural, and dreaded as beings who descended from Heaven, but it was difficult to fathom the fetish craze with which the masquerades engaged in beating themselves with juju-laced canes.

In the 70s and 80s, young folks, especially those with humble background like me, found the serenpidity of Ibadan in the nuisances of their time. Odo Dandaru in Mokola was our swimming bay, frolicking in the tidal stream and plucking water hyacinth off your head and body after each dip. On occasions, a straying baby snake was an uninvited guest. The elevator of Kingsway in Dugbe was our play ground. At age 9 and 10, with parents off to work, some of us would trek the 10 kilometers to the Cocoa House complex just to climb the elevator, up and down, in multiple times. Except for Cocoa House and one or two tall buildings, the skyline was not dotted with skyscrapers, yet the serenity of Ibadan was profound, and the security unimpeachable.

My father, Mr. Isaiah Onayoade, could read and write, gifted with one of the most beautiful handwriting I ever knew. He was an itinerant merchant who later became a farmer. Some people in the village called him Doctor. I later knew that his calling was due to his deep knowledge in traditional medicine like agunmun, aporo. It was from him I knew that wearing smoothly ironed attire with razor-blade gator was part of a gentleman’s personality. I didn’t know if gator was correct English, but I knew it was the sharp lines on a cloth after a deep ironing that the lines showed when you wore it.

My mother plied her trade at the popular Dugbe market where she was a merchant of stock fish, an affordable delight of the middle class, imported from Norway. She was popular in her own right, a semi socialite and fashion-conscious woman. She almost always had new clothes, since her group of market women, or peers in church are always having events like birthdays, child-naming and other ceremonies that must go with anko or egbejoda (uniformed party attire), with her dripping jewellery and fashion hand bags. Her two stock-fish shops were at the end of the stock-market section of Dugbe market, but asking for her from anyone at the section evoked her moniker: You are looking for Iya Kolobo? may come the cheeky response. She was known by Eeli (shortened for Elizabeth) in family circles and the neighbourhood, but Iya Kolobo stuck to her in the market after the birth of her second daughter, Iyabo, in the 70s. Iyabo was roundish and below weight, and generated some curiosity among her market clan.

Going to the market with her during school holidays was fun; playing along the labyrinth of stalls where haggling and selling was a daily life. Sometimes, we children sold some pieces at the stall, or hawking and cutting some deals that gave you extra pennies. Occasionally, you had disastrous outcomes, like tripping and losing your wares in the complexity of Dugbe market, getting shortchanged or not getting paid by some smart alecks. Dugbe was an eternal bedlam, a human jungle that nourished the poor and the rich, but more importantly, that also provided refuge for the layabouts and the itinerant merchants. It had roads, but a snail would speed faster than vehicular movements. Occasional raids by “Town Council” disrupted the human flow, and the dust settled after some financial inducements to keep the shanties on the road and wares in the drains. Besides trucks and lorries that load and offload items, you couldn’t make a leisure drive through the roads of Dugbe market.

Sometimes, I got lost in the crowd, but meandering and navigating the exodus of feet were also a plaything for a roving mind.

The other vacation time was spent in Idi Iya, a farm settlement far-flung from Ibadan City. The farm was a 2-hour walk from the Idi Iya Aba (village), including crossing a stream that was neck-high during raining season. Father, Isaiah Onayoade had a big cocoa plantation. He also planted maize and cassava, with few yam, plantain and banana. During the narrow stretch that we commuted daily during the planting season, we came across some irate monkeys or straying snakes. As father betrayed no fear during any of these encounters, my mind strayed to the possibility of chancing upon a lion or tiger; and crocodile during the stream crossings. Once I was bitten by a red ant as we walked in the dim of the evening, commonly called tomo nle, and I shouted snake bite. Tomo nle was late evening when the sun receded into a red ball at the farthest reach of sight, and the ground cast a dark shade. So, we thought it was a snake until father pulled the stubborn ant off my foot.

Sometimes, to reduce the daily long trek, we could spend about 3 days in the farm, staying under a shed made of woods and raffia palm leaves, feeding on roasted corn and yam with palm oil. Bread was also handy. Some nights were passed with small roasted bush meats, as father regaled us with stories and wisdom nuggets, one of which was the plant called Akintola taku. That weed was the most pervasive, and we children hated it because you had to cut it before any planting could take place.

Sleeping time was dreadful. Father and 2 children sleeping inside a thick bush about 10 kilometers away from human population, armed with just cutlass was an eerily awful experience. The shed had no walls and sleeping was on mat. Drifting to sleep in the dark was difficult as my eyes darted around for any strange nocturnal movement. The surrounding was pitch-dark, save for a small glowing bush fire inches away from our feet. Thoughts of an invading dangerous animal, especially snakes and monkeys, or a visit by gnomes or spirits would fill the mind until the first streak of sun rays in the morning.

The morning was good, sunny and effervescent during the dry season; and the wet season, a little chilly when it rained, but there was a freshness of the green ecosystem. Roasted corn and plantain and yam with palm oil, and bananas and oranges were the staples on the farm. But cutting the weed, clearing and burning them were a huge disincentive for holidaying at the farm. A particular weed, stubborn and tall with tick stalk, was so pervasive. It was called “Akintola Taku,” an irreverent reference to the bitter politics of the 60s between the Action Group leaders, Chief Obafemi Awolowo and the recalcitrant Chief Samuel Akintola, who disagreed with the party decision not to join the coalition government.There were other tales and folklores told in the jungle of the farm, as well as grotesque self-help practices, one of which was urinating on a wound cut to stop bleeding and kill infection. How else would a cut from cutlass or sharp tree branch be addressed when the closest neighbourhood was 10 kilometres trek of narrow pathway (ese ‘o gbeji).

In my adolescence, my mother made me love Cherubim & Seraphim (C & S) Church. She enforced active participation: the gyration and dance, the hymnals, the Easter ceremonies garnished with palm tree fronds and crucifixes, the specialised Christmas carols and drives. I was a decorated white-uniform Christian Soldier (Ajagun Igbala) at the Oniyanrin C&S parish in Ibadan where my parents worshiped in the 70s. I still remember my staff that I rolled in rhythmic harmony with the band music as I matched with my mates in the aisle of the church. But her death took the love away.

In those days, I followed Mama to some prayer grounds conducted by Prophet Obadare and Pastor Abiara in Ibadan; she prayed fervently and endlessly, that I used to wonder what she was actually looking for? But the young mind did not understand the interplay and complex mysteries of life.

Not literate, my mother desired to know the academic progress of her children. She was a beautiful woman with a good sense of fashion. She had a tattoo on her belly and arm. I still remember her gift of moderate stature and good set of teeth. She was trendy in her own way, with pouches of jewelry to boot. She was a dutiful and supportive wife. When Papa’s business went down, she paid the school fees without making a show of it (as some wives would do). She would even buy some stuff (I still remember the TV) and pretended to the children it was Papa that bought them. She believed a husband’s integrity must be protected irrespective of circumstances.

She made success of her trade. She would bring the proceeds to our rented apartment in Inalende and counted neat and rumpled Naira notes late into the midnight, separating the bundled notes in different areas of her bed. She didn’t have the pleasure of education because her parents, apparently within limited resources, decided to send only the boys to school. But her sense of accounting was remarkable, considering how she budgeted for different activities on the bed and also recorded in jotters with her awkward handwriting.

She was also renowned for her generosity and compassion. She was the rallying point of her extended family, playing the mother figure to all her siblings, including the learned ones, gifting them here and there, and offering wisdom nuggets for marital success. My uncles told me they benefited from her financial support when they were in the university. When her elder sister who lived in the village faced marital problems and abandonment, and economic hardship, she invited her to live with her own family in Ibadan along with about five of her sister’s children, all in the rented apartment. Her sister also had a seat in the stock fish market. She later built two story buildings (joined in the middle for effect) and gifted one to her sister and her family. Unfortunately, she never slept a day in the house. The house was at the plastering stage in 1984 when she died.

My Mother was an entrepreneurial survivor: There was a time her stock fish shipment was seized and her money trapped, and a time Dugbe market got burnt. And another time, the Omiyale episode (Ogunpa flood disaster) affected business and eroded profits. Not deterred, she ventured temporarily into other areas such as the kundi (was that camel meat?) market. She also lost a bungalow she built with her husband in Eleiyele area in the late 70s after the military authorities annexed the area’s expanse of land. My father fought that injustice unsuccessfully till his own demise few years ago.

Mama was a disciplinarian, never condoning indolence. If you misbehaved, she would feign ignorance of your misdemeanour and wait for you in the dead of the night when you laid prostrate in bed apparently enjoying a blissful dream, to administer your punishment. But if she responded immediately and scolded you right away, or laughed it off, chances were nothing awaited you in the night. I remember a day the “temptation” visited me. Mother had prepared an aromatic vegetable stew which the devil led me to; and took a spoonful. It was at that instant she strolled into the room. Of course it was easy to swallow the veg; the problem was that the delicacy was cooked with ata ijosin (if you know the pungent spice of this pepper), and I had to open my mouth to fan the burning sensation of my tongue. “Ah! Sanya” was her response, followed by a mischievous laughter.

The Guardian

1998 – 2003

Reporter and Journalist

British Council

2003 – 2012

Media and Communications

Sanyoyo Media

2012 – present

Founder & Principal Consultant

Commonwealth Media Award -1998

Freedom House Fellowship

University of Ibadan – Mass Communication

University of Pittsburgh – Media Training

Lagos Business School – Corporate Governance

York University – Digital Marketing

University of Toronto – Marketing